- Home

- Damon DiMarco

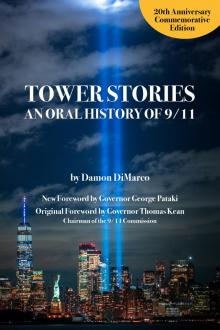

Tower Stories Page 5

Tower Stories Read online

Page 5

When the building finally settled a bit, people started running down the stairs, pushing to go past. That lasted maybe a minute before people started to scream, “Stop running, we’re shaking the stairwell!” And people calmed down again. As bad as things were, no one wanted the staircase to tear itself off the wall.

We covered our faces with napkins someone handed out. Water bottles were passed around so you could wet your shirt and cover your mouth. There was smoke in the stairwell. It wasn’t a thick cloud where you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face, but you definitely had trouble breathing.

The climb down from the 20th floor lasted an eternity. People were absolutely silent now, where before they’d been laughing, figuring the danger was in the other building. Everyone was more focused and scared, trying to walk down the steps as fast as they could.

I had stopped maybe twice on the way from floor 55 to floor 20 because it was so hot in the stairwell. I was sweating. I needed a breath. Brimley and Brian still accompanied me. They kept saying, “Okay, we’re gonna wait with you. When you’re ready, we’ll start again.” But after floor 20, I was more like, “I’m going down now, no more breaks. If I pass out on the way, it’s just gonna have to be.”

When we reached the bottom of the stairwell, we saw Port Authority workers directing us through a passageway. “Okay!” they shouted. “Make a left, then a quick right!” We followed the route they showed us through an open door, and just like that, we were out on the concourse.

I remember some people asking, “Why are you making us go through the concourse? We could have made a right and gone out to Liberty Street. Why can’t we go out those doors?” But no one was answering. Looking back, I guess we didn’t go that way because of all the falling debris.

In the concourse, there were police officers and security guards standing at different points. I feel very bad because I think they must have been left in there when the building came down, you know? They got us all out, but they were still in there.

When I saw them, it hit me that this must be something so bad. I mean, usually, what’s the protocol in a fire? The authorities tell you, “Everyone calm down, nobody run.” But here they were screaming at us, “Run! Get out! Get out! Get out!” Pointing which way to go, through the concourse, which, as I said, was a weird way to go around.

“… when our building was hit people started to scream. The impact knocked people right off their feet. I held onto the handrail with everything I had. The building started swaying so badly; it moved six to ten feet, that’s what it felt like.”

We used an escalator that made us go from the Liberty Street PATH train entrance down past the bakery, by the Nine West shoe store, and out. As we got to the top of the stairs by Nine West, there was a cop there directing us, and he said, “Things are falling. I want you to stay under the building, do you understand?”

We nodded and then he said: “Okay, now! Run! Run!”

People ran. I don’t remember things falling, though I know they were. I just kept running.

I got across the street by St. Paul’s Church, and that’s the first time I paused to look around. I’d lost Brimley and Brian, I remember that much. Were they in front of me? Behind me? I didn’t want them thinking that I was still back there; I didn’t want them going back in after me. Policemen were telling us to keep going, to run across the street, heading north, uptown …

And that was the point where I turned back and got my first look of the buildings. And I saw something that didn’t quite register to my brain. A necktie. On a man. In his suit. Jumping out of the building. I suddenly realized that people were jumping out the windows of the Towers and falling.

I was either on Broadway or Church Street, I don’t know, and I started walking up the street, walking north, past a graveyard now, the one by St. Paul’s. On the ground in front of me, there was this puddle of blood and … it looked like … a mass with shoes and clothes in a pile. I looked at it and didn’t realize for a moment what it was. A body. It had to be someone from the plane or someone who had jumped.

I said, “Okay,” and I kept moving.

A little further on, I stood up on the fence of the church graveyard so I could look back. From up high, I spotted Brian and Brimley; they were behind me, coming closer, and I flagged them down. Then the three of us followed the crowd up to City Hall.

But almost at once we all thought, what are we doing by City Hall? What if this is the next target? So we wound through the streets and the next thing we knew, we were at Federal Plaza. But the guards outside the Plaza were telling everyone, “Get away from this building! Get away!” I guess they thought it might be a target, too.

We were on Thomas Street at that point, with Brian walking ahead. We’d pass lines of people on pay phones—maybe thirty people to a pay phone—and hundreds of people fanned out behind them, standing in line, waiting their turns. They were all way too close to the buildings to suit my taste.

We passed a building and some man stepped out of a law firm. Brian asked him, “Can we come in?”

“Sure, sure.”

He took us in.

They sat us down, gave us water, and let us use the bathroom and their telephones. Everyone was trying to get through on cell phones but all the circuits were dead. I called my father in Long Island to let him know I was okay. I had to try him twice; on the third time, it went through. I probably made ten phone calls, and that’s the only one that went through.

I couldn’t get my husband. Later on, I learned that when he heard a plane had hit the first building, he went down to the World Trade Center to see if he could see me coming out. He was standing under the building when the second plane hit, trying to call me at work on his cell phone, trying to call anyone. His phone wouldn’t work so he went back to his office, which was lucky. He would have been killed when the building came down.

Brimley and Brian told me, “You stay here. We’re gonna go to the corner bar and get a drink.”

At that time, this made a lot of sense. I was like, “That sounds like a perfectly good idea.” And out they went. I guess they needed it so bad, they left the pregnant woman at the lawyer’s office. But they didn’t even make it to the corner when a police officer came to the door and started evacuating everyone from our building, too.

As we exited the lawyer’s office, we saw a building across the street where people were lined up on a huge set of steps, like a bandstand, looking up at the World Trade Center. And all of a sudden they started to scream. “Everyone! We’re gonna start to run again! Go up West Street! Get out of here! Now!”

Everyone had been calm in the lawyer’s office, the eye of the storm. Now they panicked. I started to run again but I was so dehydrated, I passed out.

Apparently, two guys from the lawyer’s office picked me up off the street. They asked the police, “Can we get an ambulance for her?”

The police said, “There’s none coming.”

One of the guys said, “Wait, I’ve got my car here.”

And the other guy said, “Put her in. Let’s drive.”

So—one guy in the back with me and the other guy driving. And as we left, the guy with me turned around, looking out the rear window, and he said, “Oh my God, there went the building.” It must have been the second Tower. I heard people screaming.

So now, at that point, both buildings were down. And these two guys drove me to St. Vincent’s Hospital.

They had hundreds of beds, rows of empty gurneys four or five deep, lined up outside St. Vincent’s with nurses standing around, waiting. I only saw one patient. Already, there were hundreds of people lining up outside the hospital to give blood. Someone had made makeshift signs that said “A,” “O,” “B,” and people were congregating around them.

They put me in a wheelchair and straight on up to the maternity ward. The doctors and nurses were concerned that I needed fluids; they wanted to see how the baby was. They said I was the only pregnant woman brought in from the Trade

Center. I looked up and saw twenty nurses milling around the nurses’ station, looking at the TV. But no one was coming, do you know what I mean? All these people were waiting, but no one was coming.

As it turns out, I was extremely dehydrated. I’d started a few contractions, but that was from the dehydration and the stress. Once they got fluid in me, everything settled down. The nurses at St. Vincent’s kept calling my husband on his cell phone until they finally got in touch with him. He came to the hospital trying to find me, but nobody knew where I was; they hadn’t been admitting people properly, so I wasn’t in the system. He started walking around trying to find me and eventually got to the maternity ward. It was probably one o’clock in the afternoon when we reunited.

It’s funny. All the lawyers in that office, Brimley and Brian, everyone had told me, “Don’t worry, your husband’s not gonna go to the Tower, he’s not gonna come look for you, he’ll just walk away.”

But I said, “I know my husband. He’s gonna look for me.” I was worried he’d be standing there at the bottom of the building. When the building collapsed and I didn’t know where he was … let’s just say I didn’t feel relieved until I saw him.

Recounting this now, it’s almost like normal. Like I’m telling a story. If you’d seen me in the beginning, though, right after it happened, I wouldn’t have been able to tell it. I’d have bawled the whole way through. I’m in counseling now. I wouldn’t say I’m a hundred percent back to normal. I have trouble going over bridges and through tunnels. But I’m slowly working myself back up. I’ve been back to the city. That was tough, but I did it.

You tell yourself, I’m a strong person, I’m tough. You never think these things could affect you the way they do.

The baby? She was having a few problems early on, but basically … she’s in there, she’s healthy, she’s on her way. At St. Vincent’s when they were looking at her on the monitor, they said, “Wow, look at that! She’s really moving around!” I figured, well, why not? I’d just walked down fifty-five flights and ran for at least a mile, and she was in there through it all, kicking around, moving. Running with me. It’s given me a connection to her.

Before, September 11, I wasn’t talking to her. I didn’t have that connection of, “Okay, little baby. Mommy’s running now. Just calm down.” Now I do.

I have to admit, a few weeks after the attack I thought, am I out of my mind bringing a child into this world? Especially, too—she was diagnosed with fluid on the brain. I thought, I’m gonna bring this child who’s possibly handicapped into this crazy world? What do I tell her? “People in this world will leave you when buildings are about to collapse. They’re not gonna help you. You’re not gonna be able to get out.” Do I tell her that if she comes out unable to walk down a flight of steps on her own? You see, my other source of guilt I have—there were so many handicapped people left in the building. They couldn’t get out. No one helped them. And they died. But I’m dealing with that. I’m getting help. I’m working it out.

Now, I definitely feel it’s important that my baby’s coming. Why should I not have a child? Why let horrible people who only know how to hate fill this world?

Fill the world with good people instead. It’s important.

Emily Anne Engoran, the littlest WTC escapee, was born on February 18, 2002, weighing in at 8 pounds 12.5 ounces.

UPDATE

Florence Engoran checked back in with me in December of 2006. She had very good news: Emily Anne now has a new baby sister, Sophia Rose, who recently turned one year old.

Florence observed that her life has changed a lot since September 11. “I try not to reflect on the nightmarish portion,” she said. “I don’t watch shows with news coverage from that day, for instance. Still can’t bring myself to watch it.”

Still, Florence noted that 9/11 helped inspire her to quit her job as a credit officer with her firm and go back to school for her master’s degree in social work. “I want to work on the issues that really caused 9/11,” she said. “Hunger, poverty, and intolerance. War won’t change these things, and I wish Bush wouldn’t use 9/11 as a reason for the war in Iraq. I think the past elections have let him know how the majority of [the] nation feels about his foreign policy.”11

Florence also added that the recent movies depicting 9/11—no-tably Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center, Paul Greengrass’s United 93, and ABC Television’s The Path to 9/11—were productions she was “displeased with.” Public sentiment seems divided on this issue. While United 93 won Oscar nominations for Best Director and Best Film Editing, the New York Times ran a story on September 6, 2006, that effectively recounted the firestorm of negative publicity and upheaval caused by the airing of that particular production.12

10 The implication here is that it wasn’t uncommon for small planes to hit the Towers. During the course of these interviews, subjects offered many supportive anecdotes to this end.

11 Referring to the elections of November 2006, in which all U.S. House of Representatives seats and one third of the seats in the U.S. Senate were contested, as well as thirty-six governorships and many other state and territorial legislatures. The final result of the 2006 elections was a massive tumult in which the House of Representatives, the Senate, and most governorships turned over from the Republican to the Democratic Party. President George W. Bush is a member of the Republican Party, and many political analysts speculated that this sudden shift in the balance of party politics reflected the American people’s disillusionment with the current administration’s policies.

12 The article was named “9/11 Miniseries Is Criticized as Inaccurate and Biased,” written by Jesse McKinley.

NANCY CASS

Nancy Cass, forty-three, worked for the New York Society of Security Analysts, Inc., located on the 44th floor of 1 World Trade Center. She was employed there for sixteen years.

8:47 A.M.

There were four of us inside one of the elevators on the east side of the building. I was the last one to step off on the 44th floor. I took four steps to my left, heading toward my office. There was a loud explosion and the building began to shake violently. People began to scatter. I froze in place, not knowing which way to turn.

One man got back into the elevator we’d just stepped off of—he looked frightened. The elevator was dark. I shook my head and told him, “No, don’t get back in.” He stepped out and ran around the corner. I heard debris falling through the freight elevator. It got louder as it came down the shaft, coming toward us, the sound like a ton of rocks being dropped through a long, long line of coffee cans. Then: a terrific swoosh, which was the freight elevator plummeting past us like a rocket through the shaft.

My first thought was that something had malfunctioned with the electrical systems on one of the higher floors. The passenger elevators on the west side of the building had been out of order for the past five or six weeks, and the elevator company had a crew of men working on the scene. I thought something might have gone wrong up there.

Then white smoke billowed out through the freight elevator doors and flames blasted through the opening.

This all happened in less than fifteen seconds.

When I saw the flames shooting through the elevator doors, I turned and calmly said, “Fire.”

The people who’d been in the elevator with me on the way up to 44 had run toward the second bank of elevators that went to the higher floors. Now they figured this wasn’t such a great idea, and ran straight for the emergency exit. I followed.

I started down the stairs, moving pretty quickly. People were already moving down in single file, and everyone was calm. But then we came to a bottleneck and had to stop; this must have been somewhere around the 39th floor.

A few hysterical women were screaming. Men in front and in back of me kept calling for people to stay calm and we began to move again, though much more slowly. We had to stop every so often to let people exiting the floors below us file out into the stairwell. And every time we stopped, I heard a w

oman from above me shout, “Why are we stopped? Why are we stopped?”

We were paused on the 35th floor when the woman called out again, “Why are we stopped?” and this time I heard someone from below answer, “The doors are locked!”

I remember wondering, what doors could possibly be locked going down an emergency exit? A building maintenance worker who was behind me asked the same question out loud. Another maintenance worker said that he had keys and started to go down, pushing his way through people.

I kept thinking, what doors are they talking about? And: Lord, I hope he has the right key.

About five minutes later, I guess they got the problem solved because the line started moving again and we proceeded down once more. At this point, smoke was starting to build up in the stairwell, souring the air with an acidic smell.

A young man two people in front of me took a travel pack of tissues from his shirt pocket. He pulled a tissue out and passed the pack to the guy behind him. I remember thinking, oh please, let him pass me a tissue!

The young man realized I was watching him. He looked at me, then handed me the pack of tissues. I took one, thanked him, and passed the packet back.

We continued down, stopping at every landing. People were still calm. Typical New Yorkers. Nothing much fazes us.

One of the men standing in the landing, three people behind me, said, “I wonder how many thousands of people are in this building.”

I answered, “I don’t know. Do you work here?”

“Yes.”

“Oh. If you didn’t, I was going to say, what a day for you to visit.”

Tower Stories

Tower Stories